Long before Columbia became the spirited river town known today for its resilience along the river, it began as a quiet settlement perched along the sweeping Susquehanna. Its transformation—from a Native American village to a national contender for the U.S. capital, to a hub of abolitionist bravery—unfolds like a frontier epic shaped by visionaries, dreamers, and the relentless current of history.

A Frontier Awakens

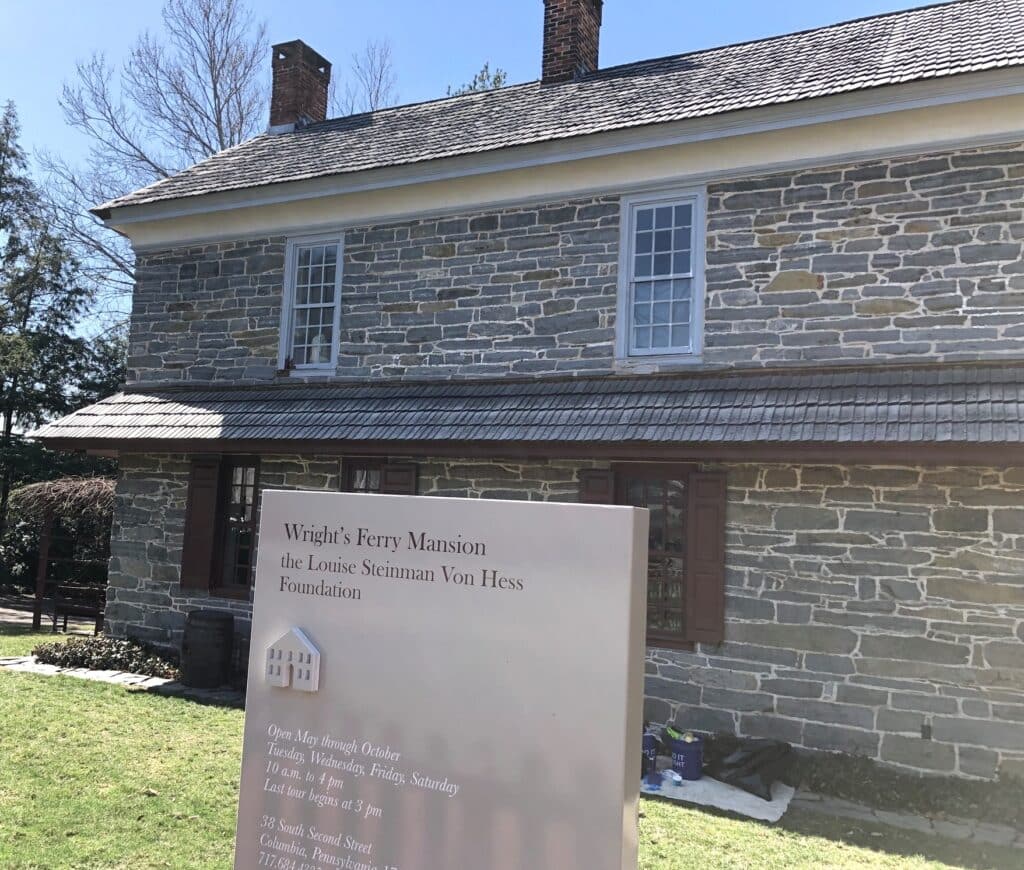

The story begins in 1724, when John Wright Sr., an English Quaker from Chester County, arrived at a Native American village known as Shanawa Town. Wright, captivated by the natural beauty and strategic location of the site, began to imagine something more. His early visits sparked a vision that would soon draw other settlers to the western bank of the Susquehanna River.

In 1726, Wright returned with fellow pioneers Samuel Blunston and Robert Barber, armed with a patent to construct a ferry. By 1730, the crossing—eventually known as Wright’s Ferry—became a cornerstone of regional commerce, connecting east and west, bringing travelers, merchants, and opportunity to the growing settlement.

Wright’s influence would extend even further. In 1729, he was appointed Chief Burgess, and in a nod to his English roots, he named the newly formed county Lancaster, after his home in Lancashire, England. Under his leadership, the once-quiet village began to gain identity and permanence.

Foundations of a Town

Wright’s legacy was continued through his children. In 1736, his son James Wright built the now-famous Wright’s Ferry House. There, his Aunt Susanna Wright lived until 1760, cultivating a reputation as both a respected intellectual and a pioneer in the region’s early silk industry. With silkworms spinning in her parlor and students gathering to learn from her, Susanna became one of the earliest symbols of Columbia’s innovative spirit.

But it was James Wright’s son, Samuel Wright, who would formally shape the town’s destiny. In 1788, Samuel surveyed the land, laid out building lots, and on July 25, auctioned them off in a public lottery. That same year, with visionary ambition, he named the town Columbia, honoring explorer Christopher Columbus. Samuel hoped the name would help secure a bold dream: to make Columbia the capital of the United States. While the honor ultimately went to Washington, D.C., the attempt speaks to the town’s early aspirations and confidence.

Battles for Freedom and Progress

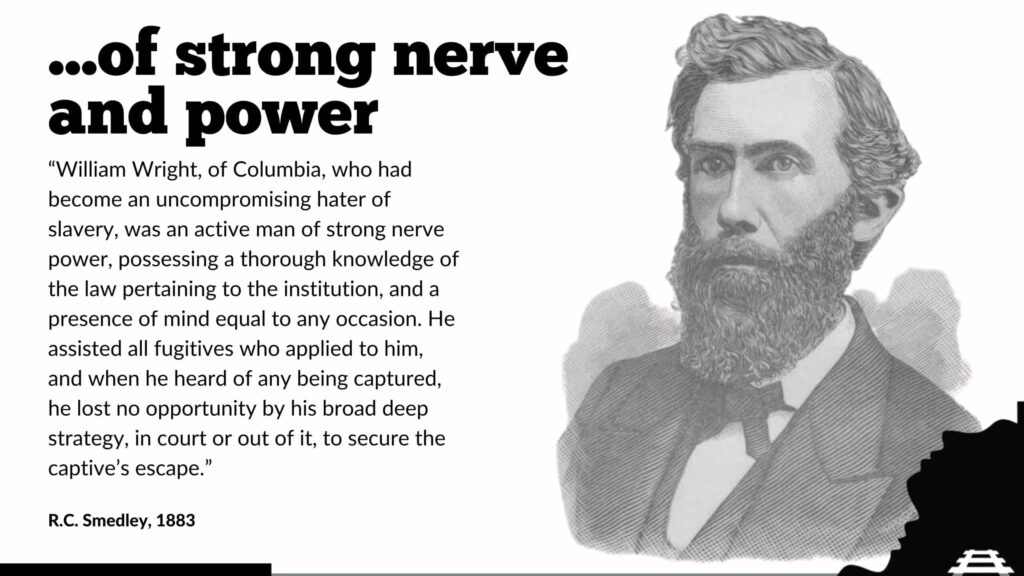

As the 19th century opened, Columbia emerged as a beacon of liberty. William Wright, Samuel’s brother and the son of James Wright, became a key figure in the Underground Railroad. Beginning around 1805, William operated a station in his own home, guiding more than 1,000 freedom seekers to safety. His quiet heroism helped cement Columbia’s place in abolitionist history.

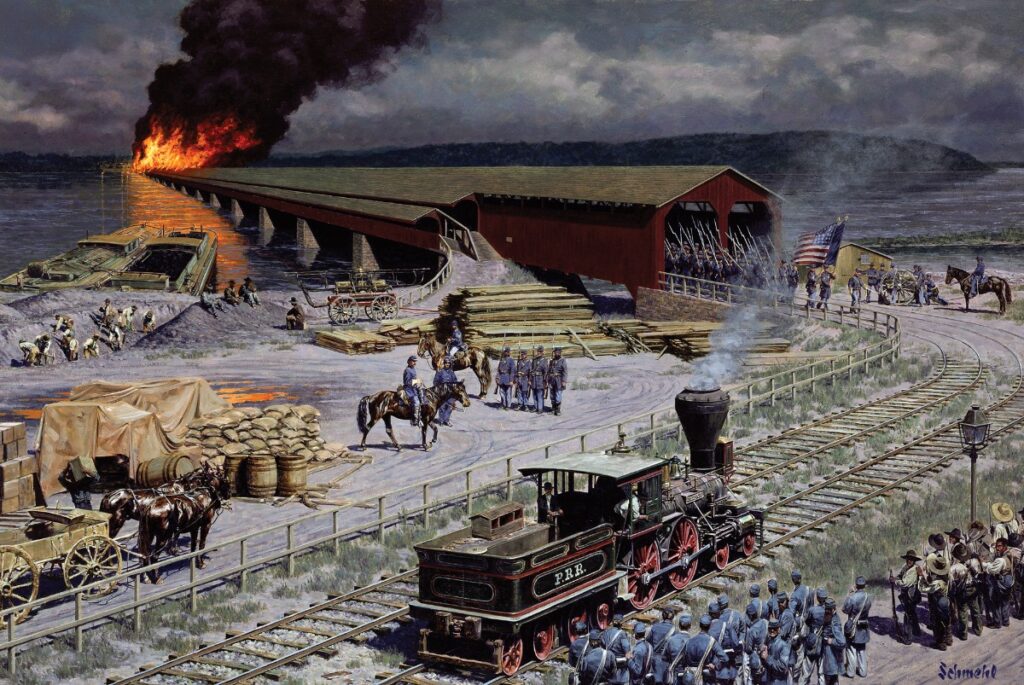

Infrastructure growth continued to reshape the town. In 1811, the Columbia Bank & Bridge Company was formed, with William Wright serving as its president. Their goal: build the first bridge across the Susquehanna. Completed in 1814, the bridge stood as a marvel of engineering until a devastating flood swept it away in 1832.

Undeterred, the company built a second bridge in 1834—a sprawling covered structure believed to be the longest in the world at the time. A “super structure” by contemporary standards, it elevated Columbia’s position as a transportation and economic hub.

Yet progress did not shield the town from turmoil. Also in 1834, tensions erupted into a violent race riot, sparked by white residents resentful of free Black workers. Homes were firebombed, and the event became a sobering reminder of the racial strife gripping the nation, even within abolitionist strongholds.

Industry, War, and the Fire That Changed History

Columbia continued to innovate. In 1846, Godfrey Keebler, who would later found the nationally known Keebler Cookie company, opened his first bakery at the Red Lion Inn on Front Street. Though he moved to Philadelphia in 1850 to expand, Columbia can claim its place as the birthplace of a snack-time empire.

But 1850 also brought the harsh reality of the Fugitive Slave Act, prompting many formerly enslaved people and free African Americans to flee Columbia for safer ground in Canada.

The Civil War soon pushed the town to the edge of another historic decision. On June 28, 1863, Confederate forces invaded nearby York County, eyeing the Columbia bridge as a crucial crossing that would allow them deeper access into Pennsylvania—and potentially toward Philadelphia and beyond.

That night, as Confederate troops advanced toward the river, five brave Columbians made a fateful choice. To prevent the enemy from crossing, they set fire to the bridge—the same monumental span that had symbolized Columbia’s growth and ambition. Flames lit the sky, the structure collapsed, and the Confederates were forced to retreat, altering their course toward Gettysburg and shaping the outcome of the war.

A Redeemed Rivertown

From its origins as a riverside village to its role in shaping national events, Columbia has continually reinvented itself. Its history is marked not only by ambition and ingenuity but by resilience—bridges burned yet rebuilt, communities challenged yet renewed. Today, Columbia stands as a redeemed Rivertown, proudly carrying forward the legacy of those who shaped it, from its earliest inhabitants to the visionaries who dared to imagine a thriving future along the Susquehanna’s shores.